Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!

Jason Kenney has been a politician for almost his entire adult life. He’s been an elected representative for more than two decades, both federally and provincially. If political success comes down to selling one’s self to voters, Kenney has shown an ability and willingness to shift his pitch and image as needed.

As Stephen Harper’s immigration minister, he shaped a persona as a forward-looking, savvy glad-hander of emigres from countries with conservative cultures. As prospective premier of Alberta, Kenney has shifted to a pickup-driving everyman with populist outsider appeal.

To better understand the man behind these personas—the man who seeks to be Alberta’s next premier—The Sprawl presents a two-part investigation of Kenney's political roots, beginning in San Francisco during the late 1980s.

SAN FRANCISCO—The University of San Francisco is a modest, quiet campus in the city centre, just six blocks uphill from the famous intersection of Haight and Ashbury. A wall separates the grounds from the street, emphasizing the private nature of the institution, and the towering, ornate St. Ignatius church brings its Catholicism front and centre.

Founded by Jesuits as St. Ignatius Academy in 1855, this religious institution was where a young student named Jason Kenney found an education that would serve him in life—not in his chosen major of philosophy, which he would never graduate from, but in a divisive brand of politics designed to elicit outrage and headlines.

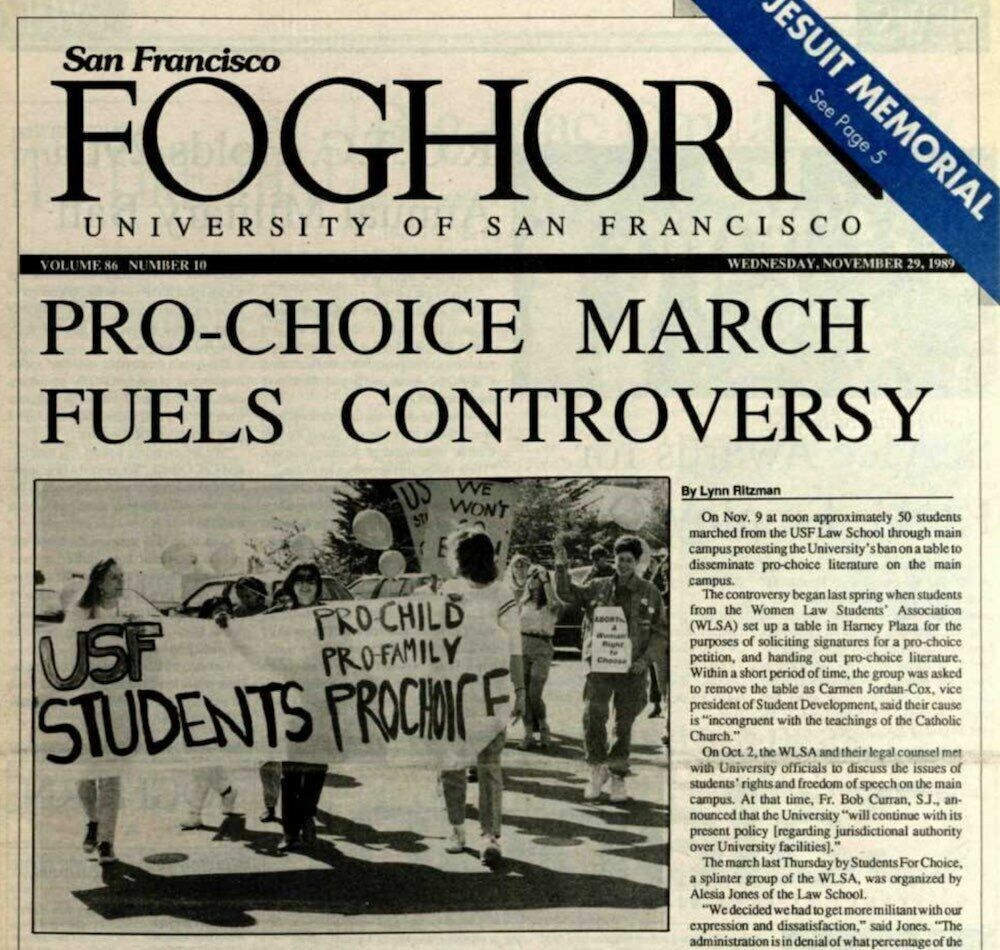

In one notable incident, Kenney seized on a conflict involving the physical intimidation by men of women who were collecting signatures for a pro-choice petition. Siding against the women, and the right to freedom of speech, a righteous Kenney turned a minor incident into a conflagration that earned national attention as he threatened to take the matter all the way to the Pope.

On March 27, 1989, Laurie Moore and two of her friends set up a table in the plaza in front of the University Center. There were a few other tables from other groups trying to advertise different things. The women, who were members of the Women Law Students’ Association, were passively collecting signatures for a pro-choice petition — not “proselytizing,” Moore told The Sprawl in an interview.

According to the account in the Foghorn student newspaper, some students objected to the presence of the pro-choice table and complained to an administrator. The administrator then told the group they had not filled out the necessary forms for the table—something Moore disputes today—and asked them to leave.

While the women were preparing to pack up and go, a group of undergraduate men approached and surrounded the table.

One of the women, Sue Ochi, told the Foghorn that the men “weren’t friendly at all. They said things to the effect of, ‘We don’t want you here. We don’t ever want you here again.’ They didn’t say. ‘We’re going to break your legs’ or anything, but the tone of their voice was very intimidating. The connotation was there.”

They said things to the effect of, ‘We don’t want you here. We don’t ever want you here again.’

One of the men, David Tognotti—now a high-ranking Google manager— acknowledged in the same Foghorn story that he told the women, “‘Whatever you do, don’t set up your table here tomorrow,’ but it wasn’t anything big.”

What does Jason Kenney have to do with this? Quite a bit.

A 2014 profile of Kenney in The Walrus, which describes this incident and quotes Moore, places Kenney among the group that intimidated the three women. Moore says she didn’t tell The Walrus that Kenney was there, as her recollection is too imprecise thirty years later to be certain of his presence or absence.

“Most of the faces are very blurry to me,” she says. “A lot of the guys were really big, and Jason Kenney isn’t that tall. That’s what makes me wonder whether he was there or not.”

Kenney told The Sprawl he was “absolutely not” part of the group.

Regardless, Moore clearly recalls two things: how threatened she felt at that table, and how Kenney seized upon a minor disagreement, escalating it in the name of morality.

Kenney was only a student at USF for three years, but he was very active on campus. In addition to writing for the student newspaper and participating in organized debates, he was elected freshman class president, as well as serving in the student senate.

The furor around the pro-choice petition would hinge in large part on Kenney’s actions in the senate. But even before the confrontation around that table, the young Canadian philosophy student had acquired a reputation for pushing hardline religious positions. In 1988, Kenney put forward a motion seeking to amend the bylaws of the student senate to require each meeting begin with a Catholic prayer. He compared it to the singing of the national anthem before sporting events.

Kenney’s proposal faced strenuous opposition, even from religious leaders like the director of campus ministry, who said he was “completely opposed” to Kenney’s proposal, adding: “Prayer is not meant to establish religious or political divisions.”

Nevertheless, Kenney pushed the motion, and remained defiant even after it was soundly rejected by the senate, calling the vote a “democratic sham.”

This episode—with its inflexible, righteous campaign to broadly assert his personal religious beliefs over the rights of others—provided a template for Kenney’s handling of the incident with Moore and the pro-choice petition.

If I look at his picture, it makes me afraid. If I hear about him having this much power, it makes me afraid.

The issue came before the student senate soon after the day of the confrontation around the table. As the Foghorn reported: “A heated debate ensued, and it grew hotter when Senator Jason Kenney introduced his resolution for consideration by the Senate.”

That resolution sought to suspend the charter of the Women Law Students’ Association, claiming it was “currently engaged in an active campaign to promote abortion rights.”

Kenney’s senatorial colleagues were not all on his side. “What are we protecting students from?” one asked. “It’s very important that we follow the Constitution, what this country was founded on, in allowing opinions to be out in the open.” But Kenney’s resolution passed by a single vote.

Kenney said, “We’re clearly and unequivocally asserting what we think.” When asked about the constitutionality of attempting to restrict pro-choice activities, he said, “There are certain absolute values that cannot be actively worked against.”

—Foghorn, April 5, 1989

The university set up a task force to study the matter, and the women contacted the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). For them, the fight was not about the question of abortion: As law students, they saw the actions of Kenney and the university as a violation of their right to freedom of speech.

Kenney put himself front and centre during the controversy that divided the campus. He moderated a debate on the issue and was regularly quoted in the student newspaper. He found a foil in Moore, who became the most prominent face for the free-speech side. Kenney and Moore opposed each other in an organized debate before a packed student audience.

“I remember being very upset,” recalls Moore. “I felt like I had to do it, but I already felt incredibly intimidated by the way the stuff was handled initially... I remember him being very vociferous and red-faced and angry.”

The Foghorn published duelling opinion pieces on the issue. Moore’s, co-authored with another student, ran under the headline “Can we talk?” Kenney’s was more alarmist: “Religious bigotry is alive at USF.”

His arguments are remarkable in their extremism. In the op-ed, Kenney refers to abortion as “pre-natal murder” and equates the pro-choice advocates with proponents of pedophilia, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Church of Satan.

But the university administration disagreed.

After the threat of a lawsuit from the ACLU, USF set forth a new policy confirming the free-speech rights of students on campus, even when advocating positions the Catholic church disagrees with.

Kenney appears to have understood this not as a conclusion but as a moral challenge. Days after the school’s new policy was approved, he led the charge to petition the Catholic church to decree that USF could no longer call itself a Catholic institution.

The move was endorsed by Kenney’s senatorial colleagues, and it was settled: Kenney would take the request to San Francisco Archbishop John Quinn.

"Organizations whose objectives are antithetical to the Gospel, including racist, pro-abortion, and homosexual groups, could soon be using facilities and resources that have supposedly been consecrated to the promotion of justice and human dignity," said Jason Kenney, Student Court Chairperson…

"Because of the unusual and sensitive nature of this petition, we expect the Archbishop to decline making a judgement," said Kenney. "We would then appeal it to the courts in Rome."

—Foghorn, February 21, 1990

In retrospect I wish I had spent a lot more time on my studies, and a lot less time on politics and campus controversies at that time.

Kenney’s escalation of the situation was significant. If church authorities in Rome agreed to strip USF of its Catholic designation, the effects would ripple through the United States, potentially affecting other religious schools.

Though it might seem fanciful that the top levels of the Roman Catholic Church would take seriously a petition spearheaded by a zealous young student like Kenney, he had an ally in Rev. Joseph Fessio, the founder of the St. Ignatius Institute at which Kenney was a student. Fessio, known as an arch-conservative, was a former student and close friend of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI who was at that time one of the most powerful men in the church.

CNN ran a segment on the controversy: Moore appears first, talking about the importance of free speech and constitutional rights, followed later by Kenney, with the words “Anti-Abortion Activist” emblazoned under his name.

The San Francisco Chronicle, the leading daily newspaper in the city, covered the row and quoted Kenney prominently as the de facto leader of the movement.

“We’re playing hardball,” said Jason Kenney, a philosophy undergraduate and chairman of the student court. “If the university is not willing to provide an educational atmosphere consistent with the Catholic faith, it should stop calling itself Catholic.”

—San Francisco Chronicle, February 27, 1990

Meanwhile, the heated situation was taking a toll on Moore. In addition to chronic meningitis—which debilitated her, but wouldn’t be correctly diagnosed until later—she was the victim of targeted harassment.

“I would go to my mailbox and there would be these horrific dead-baby postcards in my mailbox,” she says. “It was almost like when you open a thing of snakes and you jump."

"After a while, I sort of got used to it, but (it was) these desiccated dead babies in jars."

Archbishop John Quinn rejected Kenney’s petition after three months of “prayerful consideration” and legal study, declining to sever church ties with the university.

The Chronicle, noting that Kenney was the leader of the student movement behind the petition, reported:

Along with his formal response to the student petition, Quinn sent a personal letter to Kenney yesterday urging him “to recognize and appreciate, as I do, the difficulties which a Catholic institution of higher learning must face.”...

Kenney, who like most USF students has already left campus for summer vacation, could not be reached for comment.

—San Francisco Chronicle, May 24, 1990

I would go to my mailbox and there would be these horrific dead-baby postcards in my mailbox.

The vociferousness with which Kenney and his allies pursued and inflamed the issue did not sit well with many at USF. Though the university is a Catholic school, its broader culture was not as conservative as that of the St. Ignatius Institute that Kenney attended, described by the Chronicle as “an ultraconservative enclave on the Jesuit-run campus.”

The head of the USF honours program told the Chronicle that the St. Ignatius staff and students fighting to impose a strict conservative doctrine on the rest of the university were “like a bunch of Nazis to everyone else who doesn’t agree.”

A proposal to impeach the Student Senate, advanced by a professor in the theology department, accused Kenney of leading “a Pearl Harbor-type coup d’etat by a fundamentalist junta” that sought to “superimpose a closed-shop, fundamentalist and authoritarian model of Catholicism.”

The outgoing university president, the Rev. John Lo Schiavo, who approved the new free speech guidelines in February, says the campaign to overturn the policy is “mean-spirited and exemplifies closed minds.”...

Several members of the faculty and USF staff say the St. Ignatius Institute, comprising only 150 of the university’s 6,350 students, has given the university an undeserved reputation as a hotbed of conservative doctrine. They say the undergraduate Senate, which endorsed Kenney and Smith’s petition, does not represent the views of most undergraduates and note that groups representing graduate students and faculty have endorsed the free speech policy.

—San Francisco Chronicle, June 4, 1990

In the end, the student senate voted to drop the effort rather than appeal to Rome.

For reasons unknown, Kenney did not return to San Francisco and never completed his philosophy degree at USF—though a Foghorn editorial after his departure says that a university professor had publicly noted Kenney’s “academic failure and expulsion.”

But the turmoil he stirred up at USF buoyed him in Canadian conservative circles, and Kenney soon became the head of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, a newly founded organization that utilized the same style of heated rhetoric and media savvy that he’d deployed at USF. It was a short walk for Kenney from crusading religious zealot battling free speech advocates to firebrand defender of taxpayers’ pocketbooks.

From that position, he would soon launch his political career, first elected to the House of Commons in 1997 at the age of 29.

The UCP did not grant The Sprawl’s request for an interview with Kenney but provided via email Kenney’s responses to a list of questions.

Kenney downplayed his nationally-covered fight against USF and pro-choice advocates. “I have very little recollection of the details of campus controversies from 30 years ago,” he wrote. Regarding his stance against free speech, his threats to escalate the controversy to the Vatican, and his comparisons of pro-choice advocates to supporters of pedophilia and the KKK, Kenney cited youthful ignorance, saying his views have evolved.

"Like most people, my views on various questions were in flux as a teenager," he wrote. "I don’t agree today with many of the positions I took as a youngster decades ago."

He said he regrets the “ridiculous analogies and gratuitously offensive language” he used.

I don’t agree today with many of the positions I took as a youngster decades ago.

“In retrospect I wish I had spent a lot more time on my studies, and a lot less time on politics and campus controversies at that time.”

Asked about his current position on the right of Alberta women to access abortion services, Kenney responded by talking about the UCP’s focus on jobs and the economy. He went on to say that his party has “no intention of re-opening the abortion debate.”

Even after three decades, Laurie Moore still feels affected by the whole ordeal.

Jason Kenney is not a name that often pops into her life in San Francisco. But when a news story enters her view—or a reporter knocks on her door—it all floods back.

“I think I have a visceral reaction, which is interesting to me,” says Moore. “When I hear about him, I feel afraid. I feel... It’s just devastating. It’s devastating that he’s gotten to where he is, for me. Do I have a right to judge that? I don’t know the answer."

"If I look his picture, it makes me afraid. If I hear about him having this much power, it makes me afraid.”

When I hear about him, I feel afraid… It’s devastating that he’s gotten to where he is, for me.

Those lingering feelings, and the heated conflict that produced them, trace a long path back: before the ecclesiastical petition, before the CNN segment, before the Chronicle articles, before the senate votes and speeches and calls for impeachment, back to a relatively minor disagreement over a table at a student fair.

“Somebody has to be pretty rabid about that particular issue and very wedded to it to be able to transport what was essentially a pretty benign thing into this huge conflagration,” says Moore.

“I’m a human being, and this affected me. It was horrible for me.”

“And I would like him to know that, I guess. There are consequences to what you do.”

Taylor Lambert is a Calgary writer and the author of Darwin's Moving, which won the 2018 City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. But we can't do it alone. If you value our work, support The Sprawl so we can keep digging into municipal issues in Calgary!