Illustration by The Sprawl

The downsizing of Calgary’s Green Line

And the upscaling of the Flames’ new arena.

Sprawlcast is Calgary’s in-depth municipal podcast. Made in collaboration with CJSW 90.9 FM, it’s a show for curious Calgarians who want more than the daily news grind.

If you value in-depth Calgary journalism, support The Sprawl so we can do more stories like this one!

The short version

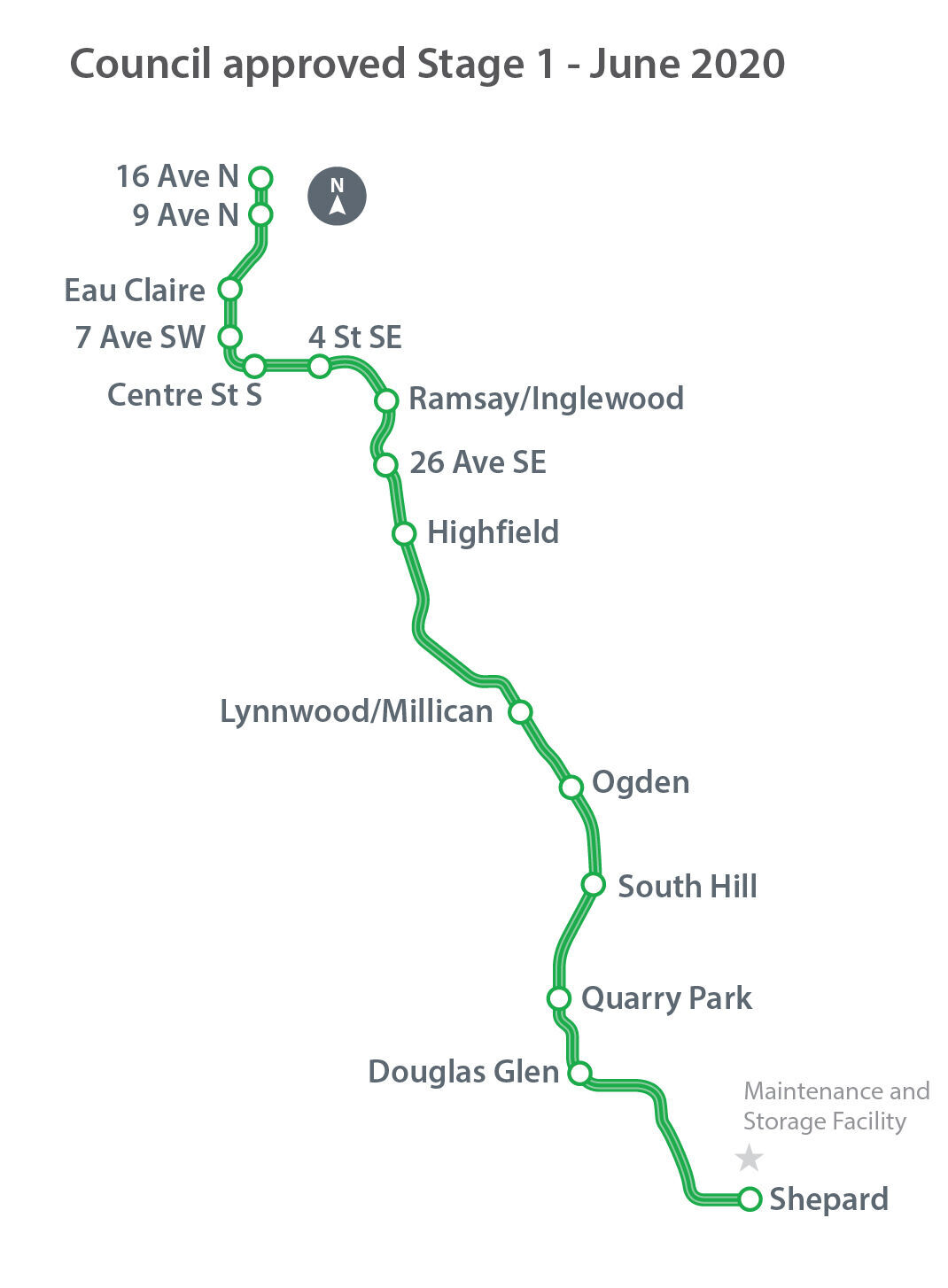

- When Calgary city council originally approved the Green Line LRT alignment in 2017, the plan was for a 20-kilometre stretch that would run from 16 Ave North to Shepard in the southeast, tunneling under the Bow River and downtown. The cost estimate was $4.65 billion, split between the municipal, provincial and federal governments.

- City hall planned to open the Green Line in 2026 and expand incrementally north and south—eventually running a full 46 kilometres—like the CTrain did after its 1981 opening. But after years of delays, no track has been built despite city hall spending over $1.3 billion on the project so far.

- In 2020, after city hall re-evaluated the project scope, council approved a revised alignment with a bridge over the Bow River, rather than a tunnel beneath, with the cost pegged at $5.5 billion.

- In 2021, after the city paused construction procurement in response to a provincial review of the project, the Green Line board approved a new procurement strategy with Phase 1 running 18 kilometres from Eau Claire to Shepard.

- In July 2024, a week after the groundbreaking for the new Flames arena, city council approved a downsized Green Line Phase 1 of 10 kilometres for $6.248 billion, citing inflation and cost escalations. The city has increased its share of the total cost to $2.9 billion.

- City hall put $1.45 billion into three other major capital projects: the new Flames arena ($853 million), the BMO Centre ($333 million) and a new Arts Commons building ($270 million). City admin says the Green Line can only go from Eau Claire to Lynnwood/Millican with available city funding. Six stations have been cut; seven remain.

- To build the first phase to Shepard, as planned, would have cost an additional $1 billion, according to Green Line board chair Don Fairbairn—“a billion dollars of funding that we don't have.”

The full version

COUNCILLOR KOURTNEY PENNER: I just want to acknowledge that there is disappointment in the decision that we've made today.

JEFF BINKS: It has been 10 years of design, debates and delays when it comes to building the Green Line.

MAYOR JYOTI GONDEK: More than 300,000 people have moved here and we have not expanded our LRT system by one metre.

COUNCILLOR GIAN-CARLO CARRA: And the reality is that if we don't do this now, with the money that we have committed, we will never connect the north with the south.

JEREMY KLASZUS (HOST): It’s been an eventful summer for Calgary city hall’s two largest megaprojects.

IAN WHITE (CTV CALGARY): Breaking news at city hall! Calgary's biggest construction project ever will now be shorter before major work has even started.

KLASZUS: The Green Line is envisioned as a 46-kilometre LRT line that will go from the city’s far north to the Seton hospital on the southern edge of the city—one day. Nearly a decade after federal funding was first announced for the project, no track has been built yet, and we’ll get into that.

But we can’t talk about city hall’s biggest capital project without also considering the second-biggest one.

TARA NELSON (CTV CALGARY): We now know what the new home for the Calgary Flames will look like and what it will be called. Scotia Place was unveiled this afternoon, and it is a massive project set to transform Victoria Park.

KLASZUS: That project is now under construction. The city is putting up $853 million for it up front; the Flames are putting in a fraction of that, $40 million, to start, with $316 million more being paid to the city by 2060. And at the arena groundbreaking on July 22, the mood was jubilant.

PROMO VIDEO: It will be a landmark attraction in our downtown and the emerging culture and entertainment district.

KLASZUS: The mood was significantly less buoyant at city hall a week later on July 30, at the last council meeting of the summer. That’s when city council approved the downsized plan for the Green Line—or, as some have been calling it, more of a Green Stub.

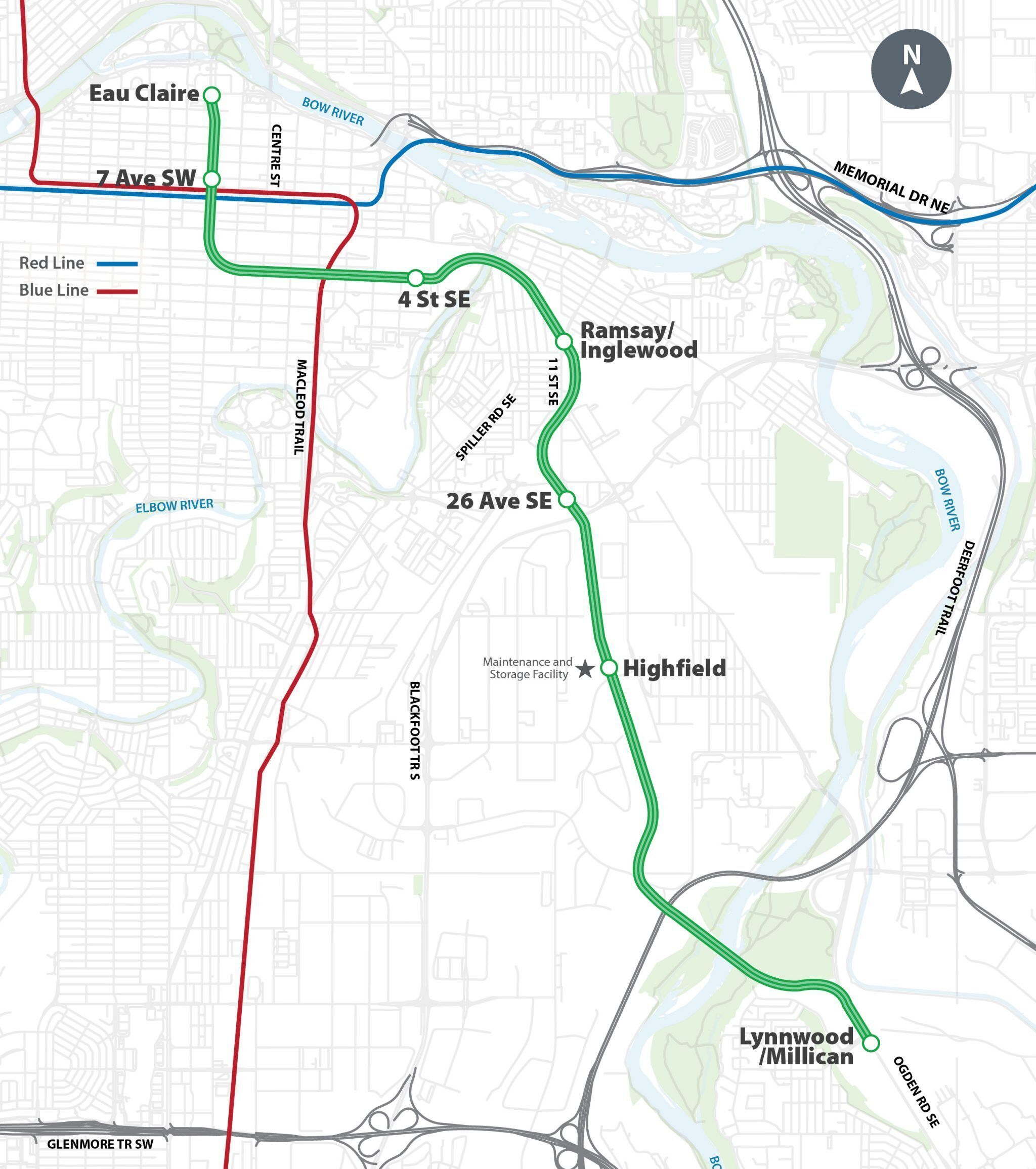

The first phase was supposed to run from Eau Claire, east under downtown, and southeast into the neighbourhoods of Ogden, Riverbend and Douglas Glen—ending at Shepard. It was going to be an 18-kilometre track with 13 stations, carrying between 55,000 and 65,000 Calgarians daily.

But the downsized plan approved by city council won’t take the line that far south. It’s been nearly cut in half, going only 10 kilometres to Lynnwood/Millican. It’s not even going all the way into Ogden.

Ask anyone in finance. If you hold onto cash for a decade, inflation will erode your buying power.

KLASZUS: Six stations got cut. The expected opening day ridership has dwindled to 32,000. And this downsized line is expected to cost $6.2 billion, up from $5.5 billion.

MAYOR GONDEK: Ask anyone in finance. If you hold onto cash for a decade, inflation will erode your buying power. Pile on an historic run of inflation over the past four years, and those dollars have even less buying power. That’s what we’re looking at today.

KLASZUS: Here’s Green Line board chair Don Fairbairn speaking to council July 30.

DON FAIRBAIRN: I understand the disappointment that some Calgarians will feel that the line is being built in phases and will not be built to serve their community when they had thought it might be.

KLASZUS: In this episode, we’re going to dig into what happened—and look at how one city megaproject has affected the other. It’s a story I’ve been following since 2019, when I did a couple Sprawlcast episodes on how city council prioritized a new arena over the Green Line. And one could argue, five years later, that not much has changed.

But at the same time, a lot has changed. The city has grown explosively, and the scale of these two projects has also changed dramatically. Since 2019, one megaproject got a lot bigger—and one just got a lot smaller.

The Green Line's delay-plagued history

To understand the current situation, we need to go back to the early 2010s. That’s when city hall started pursuing a new LRT line for Calgary that would join the north and the south. A line that would complement the CTrain system that opened in 1981 and expanded many times in the 30 years after, becoming one of the most-ridden LRT systems in North America. More than 270,000 people ride the CTrain every day.

SHANE KEATING: When I first joined council in 2010, this project was hardly on the radar.

KLASZUS: This is former councillor Shane Keating speaking about the Green Line in May 2017. Keating championed the project and considers himself the father of the Green Line.

KEATING: In 2013, we were talking about a dedicated bus lane for the southeast and part of the north-central. Today, we are on the verge of breaking ground on one of the most important projects in Calgary's history.

KLASZUS: The Green Line would be different from the CTrain. It would have low-floor LRT cars and the stations would be better integrated into streets and neighbourhoods. It was often described by city hall as a “city-shaping” project as opposed to a bare-bones train line. Here’s how former city councillor Druh Farrell put it in 2019.

DRUH FARRELL: This is not just transport. It's not about a commuter rail getting people as quickly as possible through the city. It's about creating a city around transit, and that's exactly the way we should be looking at this, is using transit to influence how our city develops and changes.

KLASZUS: City hall’s initial spitball estimate, in 2015, was that the 46-kilometre line could be built for $4.5 billion—but this soon proved unrealistic. Vigorous debate ensued about whether the line should go north or south first. And in 2017, city council officially decided on the south, approving a 20-kilometre alignment from 16 Avenue North to Shepard in the city’s southeast. And this stretch was estimated to cost no more than $4.65 billion, with the cost split between municipal, provincial and federal governments.

FABIOLA MACINTYRE, CITY ADMIN (2017): Our target is to start construction by 2020 and open by 2026.

KLASZUS: At the time, city hall was planning to tunnel beneath the Bow River north of downtown. But that plan soon changed, delaying the project.

MICHAEL THOMPSON, CITY ADMIN (2019): We believe that the risks of going underneath the river with the tunnel that we were looking at, and the station construction we were looking at, are too great.

KLASZUS: In 2020, after city hall re-evaluated the project scope, council approved a revised alignment, with a bridge going over the Bow River and the train running at grade on Centre Street instead of tunneling beneath. There was also a station added for Crescent Heights, and the cost for 16th Avenue to Shepard was now pegged at $5.5 billion.

Our target is to start construction by 2020 and open by 2026.

KLASZUS: Throughout this process, concerns were raised by a group led by retired oilman Jim Gray about tunneling under downtown. They argued the Green Line was too risky.

JIM GRAY (2019): If we stumble on this, it'll take this city down—not just fiscally, but our reputation will be lost.

KLASZUS: More delays came when the province reviewed the project in 2020, and procurement for the first segment was paused by the city amid the funding uncertainty.

NAHEED NENSHI: Minister McIver made us do another look at the project. Ended up approving the project as written, but delayed us two years.

KLASZUS: This is what former Calgary mayor Naheed Nenshi told me in May, shortly before he became leader of the Alberta NDP.

NENSHI: In those two years, interest rates went through the roof, and construction cost inflation was massive. So the actual cost escalations are their fault.

KLASZUS: More recently, current Alberta transportation minister Devin Dreeshen has called the Green Line a Nenshi “nightmare,” and indicated that the province won’t add any more funding for the project, at least for now.

But while the Alberta NDP is gung-ho about the Green Line today, that wasn’t always the case. When the NDP was in power, it was initially slow to fund the project—a climate-friendly train line that was expected to take 6,000 cars off the road each day—even as the NDP government put billions into Calgary’s and Edmonton’s ring roads.

The federal Conservatives had announced $1.5 billion for the Green Line in 2015, and it was another two years before the Alberta NDP government came to the table with a matching $1.5 billion in 2017.

JEFF BINKS: Anybody who’s pointing fingers at this point in the project better have a mirror handy, because nobody is completely blameless.

KLASZUS: This is Jeff Binks with LRT on the Green, a pro-Green Line advocacy group. He’s been following this project for over a decade.

BINKS: This project has seen politicians from across the political spectrum weigh in on it. And we’ve had conservative governments, NDP governments, liberal governments. We’ve had multiple different councils, different mayors, different councillors. We’ve had different project managers. We’ve had different people in charge of the City of Calgary.

I can’t see any one party taking blame because everybody’s made a contribution, and everybody, through those contributions, have also introduced an element of delay or indecision.

And unfortunately, we’re seeing the consequences of it.

Anybody who’s pointing fingers at this point in the project better have a mirror handy, because nobody is completely blameless.

While Green Line stalls, arena speeds ahead

KLASZUS: In May of 2021, city hall eventually settled on building from Eau Claire to Shepard for the project's first phase.

Meanwhile, as the Green Line went through various stages of limbo and delay, something similar was happening with the arena deal. In 2019, city council agreed to pay $290 million for a new NHL arena, splitting the costs 50/50 with the Flames. But that deal fell through in 2021.

City council approved a new arena deal in April 2023, with the city putting in $853 million up front—nearly three times the amount of the original deal.

And while the 2019 deal had some of the naming rights revenue going to the city, that’s not the case in the new deal for Scotia Place. Here’s Bob Hunter, the city’s lead on the arena project, speaking at the groundbreaking in July.

BOB HUNTER: It is a CSEC right. They own the rights. They own the revenue. And they would have negotiated directly with Scotiabank.

KLASZUS: Here’s Flames CEO Robert Hayes.

ROBERT HAYES: It's a great deal. It's a long-term deal is all that I will say. Scotiabank is immensely pleased. Had some correspondence with their CEO over the last 10 days. Very excited about what the future holds for the partnership.

It’s a great deal. It’s a long-term deal is all that I will say. Scotiabank is immensely pleased.

KLASZUS: City hall has portrayed the arena deal as something that won’t compromise city finances elsewhere. Here’s city CFO Carla Male at budget week in November.

CARLA MALE: None of the current funding sources identified for the event centre project and district-wide infrastructure improvements will result in an increase in municipal taxes and no new debt for the city.

KLASZUS: But as University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe told me in October, this isn’t the whole story.

TREVOR TOMBE: It’s definitely not a free lunch. There are costs because we’re foregoing the opportunity to use those funds for other purposes.

KLASZUS: I asked CFO Male about this in May, when I was reporting on The Real Costs of the BMO Centre.

MALE: The comment that we make choices over time—he’s absolutely right. Whenever we take a look at any major capital project, be it this one or many of the other capital projects—transportation infrastructure, any of those projects—we take a longer look out at the options, the available funding, and the financial capacity. And we make recommendations so that council can make these large decisions understanding the longer term impacts, as well as the choices that they have at hand.

KLASZUS: This happened publicly for the 2019 arena deal. It was presented and debated at council. But this time around, the deal was not presented or debated publicly at all. All 15 members of council voted unanimously to approve it, after discussing it behind closed doors.

Sonya Sharp is the councillor who led the push for the new arena deal. In June, the Bearspaw water feeder main burst in her ward. And in July, Councillor Sharp suggested in an interview with Calgary Sun columnist Rick Bell that her council colleagues were getting distracted by shiny stars rather than focusing on the basics of municipal government.

At the arena groundbreaking in July, I asked Councillor Sharp about this. And just a heads up that I mistakenly referred to it as a “grand opening.” It obviously wasn’t a grand opening—that’s not expected until 2027. What I meant to say was groundbreaking. Anyway, here’s our exchange.

KLASZUS TO COUNCILLOR SHARP: I was reading the Dinger—my colleague, the Dinger—last week, and you said in an interview that some of your colleagues are getting distracted. They’re getting distracted by shiny stars, and they’re not focusing on the basics of what needs to be provided by municipal government. Water, sewer, garbage, roads, all that stuff. So, I’m curious. Here we are, grand opening of what is arguably a very shiny and expensive star. And I’m curious how you square those things.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: Sure. Well, I’ll say this. This was an approved capital project in 2019 that fell off the rails right after we got elected. This is an infrastructure project, amenity-building project for this community that was already on the books, and it needs to get done. So is this critical infrastructure? Sewer, water, that’s important, but so are buildings like this. We draw people in from all around the world, and if we’re not building facilities like this, how are we going to keep Calgary and Calgarians here?

So this is—I wouldn’t call this a new shining star. This has been sitting on a capital project with BMO, Arts Commons, event centre, and Green Line to come. So we’ve got to build these projects to keep Calgarians here, and bring people around the world to invest in our city.

KLASZUS: But just to be clear, it was the old price tag on the books, right—this one, three times as much that the city is putting in. So it is new in that sense.

COUNCILLOR SHARP: It’s a new project. Yeah, it’s a new project; we won’t say that it’s not. We can’t compare it to the old project, and I think we need to stop. I think we need to move forward, leave the other project alone, and move forward. We are getting more for our money, and we have also the province investing money that wasn’t on the books last time.

If we’re not building facilities like this, how are we going to keep Calgary and Calgarians here?

'Available city funding' can build only 10 kilometres

This brings us back to the final week of July and the shrunken Green Line. Here’s city CFO Carla Male.

MALE: Green Line is a council priority, and administration has worked diligently to provide the best funding solution possible for Calgarians using available city funding.

KLASZUS: Available city funding gets us the 10 kilometre version. And even those 10 kilometres have been downgraded, with the 4th Street station by the arena brought to the surface. This is partly to tie in with a potential “Grand Central Station” envisioned by the provincial government in its plans for an Alberta passenger rail network. Meanwhile, another Green Line station at Centre Street has been eliminated for now. Here’s Green Line public affairs director Wendy Tynan.

WENDY TYNAN: It's a cost-savings piece for sure. At this time, we will continue to build the tunnel through where that station would be and put in the infrastructure to be able to ensure that a future station could be built as that area gets developed out.

KLASZUS: So how much would it cost to do the full 18-kilometre stretch to Shepard as originally planned? Here’s what Green Line board chair Don Fairbairn told reporters.

FAIRBAIRN: I think it's fair to say that it was broadly a billion dollars more. And a billion dollars of funding that we don't have.

KLASZUS: So if the city hadn’t gone big on the Flames arena, would this be a different story? Without the arena expenditure and either the BMO Centre or Arts Commons expansion, you have that billion dollars and more. And I asked Mayor Gondek about this.

MAYOR GONDEK: So when we were contemplating the event centre, this information was not before us because it was a different moment in time. And as a city, we need to be able to do multiple things at once.

To get the event centre done is significant in terms of getting energy going into the Culture and Entertainment District in order to make sure that other investments are coming into play; to ensure that the hotels and commercial and residential growth that we need to see there is spurred on by a catalyst like the event centre.

When it comes to the Green Line, this is a particular moment in time where we have been brought forward the reality of cost increases.

When we were contemplating the event centre, this information was not before us because it was a different moment in time.

KLASZUS: I also asked Councillor Evan Spencer about this. The line is falling short of neighbourhoods in his ward. He’s pushing for the line to reach those neighbourhoods soon as possible, and he’s been open about wondering whether the decision to approve the arena was the right one.

COUNCILLOR EVAN SPENCER: If we had all the information that we have today, no doubt a few councillors would have approached that decision differently. But the simple fact of the matter is we didn’t have that information.

The project hit some pretty choppy waters. We didn’t know up until the very, kind of zero hour at the end of the line of the preparation work—we didn’t know that the province wasn’t going to be interested at all in adding extra funding onto it, right, and that they were going to hold the line, and not allow for extra funding from the province.

So that changed the whole outlook, and if we’d known those things, likely you would have seen us approach some of those other capital decisions differently.

If we had all the information that we have today, no doubt a few councillors would have approached that decision differently.

Why councillors voted how they did

As the price tag for the Green Line has goes up, the city has increased its share of the total cost to $2.9 billion.

We’re going to listen in now to what city council members had to say on July 30 about the new Green Line alignment, which council approved 10-5. We’ll start by hearing a few of the councillors who voted against it.

Here’s Councillor Jennifer Wyness, followed by Green Line board chair Don Fairbairn. Wyness was asking why build in the core—and not start with a section further out, where the need is greater.

COUNCILLOR JENNIFER WYNESS: Could one not argue that we’ve kind of already oversaturated or built the core with trains? You’ve got your Red Line; you’ve got your Blue Line—even some of your Green Line is a walkable distance from the Red Line. I’m just kind of curious again how a very saturated rail market is not going into new territory, where we could really get a ridership up as a phase one.

FAIRBAIRN: Right. So our view is: Build the core. Build the downtown section from Eau Claire through to Millican. That is the best option from which to build incrementally phases north and phases south.

COUNCILLOR ANDRE CHABOT: I just can’t see the cost benefit for this kind of an investment for so few new riders. The amount of revenue that’s going to generate is nominal... It’s got projections on how much it could facilitate as far as new development is concerned, but we’ve got numerous existing LRT lines with a significant amount of redevelopment opportunities currently in the queue.

The idea that this is going to add so much more, and there’s going to be so much market absorption on this new line, begs the question of: Are we saturating the market? There’re a lot of reasons why I just don’t see this as the best solution going forward.

I just can’t see the cost benefit for this kind of an investment for so few new riders.

COUNCILLOR SONYA SHARP: If you were generally in favour of building transit, you would not have been starting with the most expensive, riskiest part—and barely adding ridership. What Calgarians might see, and what I see, is risk. There’s a financial risk, a risk that’s not just for the city, but for Calgarians.

And honestly, you can spin this any way you want, but I will not support burdening Calgarians on top of maybe the fiscal integrity of the corporation. This project does put other future projects at risk.

I’m not against the Green Line, but I would have liked to have seen the money go towards a portion of the line that would have tied into the Red Line and Blue Line and better serve the south. I have confidence to say that I think this project lost its value proposition. So with that, I won’t be supporting this.

I have confidence to say that I think this project lost its value proposition.

KLASZUS: Now we’ll hear some of those who voted for it.

MAYOR JYOTI GONDEK: I don’t think we can lose sight of the fact that we are voting on a phase of this project today. There’s still a whole shwack of it left to build. And so I think it’s incredibly important to make sure that we pass these recommendations.

COUNCILLOR COURTNEY WALCOTT: When I think about the history of the Green Line—just as a citizen, or as an elected official—I think the story has always been a simple one. Which is, the tactic to make the Green Line go away was never to say no to the Green Line. Never to say that this isn’t good for this city. That has never been the tactic. Rather, the tactic has always been, for those who are opposed to it, delay it until it was so expensive that no one could handle it. That was always the strategy—delay it.

What we’re doing here today in particular, and what this council kind of should be able to stand very proudly on, is the idea that we’re not really willing to accept any more delays.

The tactic has always been, for those who are opposed to it, delay it until it was so expensive that no one could handle it.

COUNCILLOR GIAN-CARLO CARRA: We have an unprecedented amount of money committed to this project. It’s three times larger than the largest infrastructure project we’ve ever tackled, and it’s buying us less now. But because we have that amount of money, we have to tackle the hardest part of this project.

When we were first conceptualizing connecting the north with the southeast, the two big regions of the city that were not served by transit, we did not recognize how difficult it would be to get through the downtown. With the CP rail, the river, the short blocks, the short distance, the escarpment on the other side of the river—all of that is incredibly difficult.

And the reality is that if we don’t do this now with the money that we have committed, we will never connect the north with the south.

COUNCILLOR TERRY WONG: This is the equivalent of building a chassis to the ultimate engine. You don’t start with building the roof or the trunk. This is the starting point.

COUNCILLOR PETER DEMONG: There will never be a cheaper time to build the Green Line than today.

COUNCILLOR JASMINE MIAN: I think one of the biggest challenges on the Green Line has been its vision. It has a beautiful, beautiful vision, like all the rest of our lines do. And it has to start somewhere, and I recognize when we show people the beautiful future vision map, they want to see that built today. And I do too, but I think what’s really critical in these recommendations is that we’re building the most essential and core part of this line.

There will never be a cheaper time to build the Green Line than today.

COUNCILLOR KOURTNEY PENNER: If this was an easy decision, we would have made it months ago. It has been difficult. We’ve had difficult conversations with our partners at the Green Line team, we’ve had difficult conversations with administration, we’ve had difficult conversations with each other, but we had to make a decision. And I’m really proud of the decision that we made today to get going on that.

So I just want to acknowledge that there is disappointment in the decision that we’ve made today, because it is not what Calgarians are expecting and were promised, but I think they should take heart in the commitment from those of us around this horseshoe and on the other side that this isn’t the end; that this is a beginning, and we really need to continue.

COUNCILLOR EVAN SPENCER: After nearly a decade of delays and setbacks, this project is moving forward, and I want us to immediately begin thinking beyond the core. While this is super important, and I agree with what Councillor Carra—a bunch of his points about just the necessity of getting the downtown figured out, the necessity of doing the open heart surgery that’s going to increase the viability of this project into future iterations, into future extensions—we need to be immediately thinking about tomorrow.

If this was an easy decision, we would have made it months ago. It has been difficult.

For Green Line boosters, a 'bittersweet' win

KLASZUS: Like the arena deal, the Green Line has been handled very secretively at city hall as costs have gone up. For months, council has been meeting behind closed doors with the Green Line team and board, until council had no choice but to make a public decision before its summer break.

So with costs increasing so dramatically, why not consider other options—like an elevated line through downtown, rather than sticking with the tunneling plans? Questions like this have been discussed. But Green Line CEO Darshpreet Bhatti, who took over the Green Line project in 2021 after significant turnover, told me it’s not that simple, for a number of reasons.

DARSHPREET BHATTI: Those questions were obviously raised by elected officials a third time around, and we said: Everything is doable, but all things have implications. So if the objective is to build Green Line, then we also need to respect the work that’s been done already, and not reinstate it again. So as you know, five, six years is not a small timeframe to be able to go through all those permutations, land on a decision. And then to go back and to rehash all of that actually wouldn’t bring anything meaningful to the public.

KLASZUS: The city has already spent over $1.3 billion on the Green Line so far, including on utilities relocation work downtown and an underpass project in Ogden to make way for the new LRT. Even though the line isn’t going there yet, that work will continue. Proceeding as planned also means the city can hang on to its current contractors, says Bhatti, rather than rebooting procurement yet again.

To go back and to rehash all of that actually wouldn’t bring anything meaningful to the public.

BHATTI: Two years of escalation alone will be worth more than whatever you're saving now. So you have to take all of those aspects into account. That you don’t have a public process that supports this new option. You don’t have the funding partners that have supported that new option because all of our funding is based on an approval. You need to design at a certain level to be able to go back to market. You’ve lost your current procurement, so we would be going to the market for the third time.

We already had significant challenges just bringing in the partners we do today after the previous cancellation. So the third time around, as an owner—I’m speaking very frankly—you would lose your leverage because the market would see you as a noncommittal owner. They would see you as an owner that’s changed their mind multiple times.

KLASZUS: But while the Green Line is much shorter than hoped, it’s still being hailed as a win by project boosters.

BINKS: It’s bittersweet. Sometimes in the moment, a win feels like a loss.

KLASZUS: This is Jeff Binks of LRT on the Green.

BINKS: It has been 10 years of design, debates and delays when it comes to building the Green Line. And what we finally saw with council’s decision is we’re actually going to build it. And I think that’s a huge step forward.

People are looking at this construction project in a very linear fashion—we’re starting on stage one, we’re gonna build at Eau Claire, and we’re going to end up at Millican, and that’s going to be it. And we’re going to open it up, and people are going to hop on the train, and we’re going to talk about what’s next.

And I think people forget that we’re looking at a six to seven year construction timeline for this project and the downtown tunnel, which is happening as part of stage one, is going to be the most complicated part of the construction build. It’s going to take the greatest amount of time of this construction build. And so, as those tunnels are being built, as those excavations are happening in downtown Calgary, that gives us a couple of years to talk about more funding and what can be done with it.

What we finally saw with council’s decision is we’re actually going to build it. And I think that’s a huge step forward.

KLASZUS: It’s worth remembering that the CTrain was built incrementally, not all at once. It opened with 11 kilometres in 1981—and then it expanded over thirty-plus years, adding up to the 45 stations and 60 kilometres we have today. And proponents are hoping the Green Line will be similar.

BINKS: Yeah, it’s not the shiny project we were all hoping for, but I think we’re really building a solid foundation that we can continue to expand outward with. And eventually, one day, we’re going to hit that 44-kilometre line from Keystone to Seton, and it’s going to be an incredible project for Calgarians, delivering amazing benefits.

Jeremy Klaszus is the founder and editor of The Sprawl.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. If you value independent local news, support our work so we can keep digging into municipal issues in the run-up to the 2025 civic election—and beyond!