The Bow River on July 19, 2024, as wildfire smoke descends on Calgary. Photo: Jeremy Klaszus

The ‘distant future’ is upon us

As wildfires rage, our water is also vulnerable.

On weekends, The Sprawl sends out an email newsletter called Saturday Morning Sprawl. We post some of these here so they can be read and shared more widely. Subscribe here so you don't miss a dispatch. Here is this week's edition.

Earlier this year, in February, I emailed the city of Calgary with a simple question: Where does our water come from?

"You turn on the tap in your Calgary home to pour a glass of water," I wrote. "Where does that water come from and how does it get to your house? What happens to it en route? I want to know the entire process."

My idea was to follow a drop of water from its headwaters in the mountains all the way to our taps.

So I did a couple interviews but got busy with other projects. The water Sprawlcast simmered in the background. Then, in June, the Bearspaw south feeder main—which carries over half of the city's treated water supply—ruptured.

At first, I thought to myself: Dammit! I should have got cooking on that water story. I could have had a whole Sprawlcast about Calgary's water infrastructure all ready to go.

But when I went back to the interviews I'd done earlier this year, I realized how timely they were—and how little the long-term precarity of Calgary's water supply has to do with our pipes.

Even the best water pipes in the world will be of little use if we don’t have enough water to fill them with.

For as long as I've been a journalist in Calgary, the issue of water shortages in southern Alberta has been a looming issue. But it's always seemed far off, never something to worry too much about in a big, prosperous city like Calgary.

In 2006, anticipating water shortages, Alberta's Conservative government closed much of Southern Alberta water basins to new licenses. In 2007, after years of pleading with Calgarians to use less water on their lawns (and sidewalks... and driveways... ), the City of Calgary warned bluntly that "it’s increasingly obvious that our city’s current water use is not sustainable."

That was nearly two decades ago. Even so, these warnings didn't register with any real urgency. Hotter days, water shortages, the life-altering impacts of climate change—they were some problem in the distant future.

But the "distant future" is upon us.

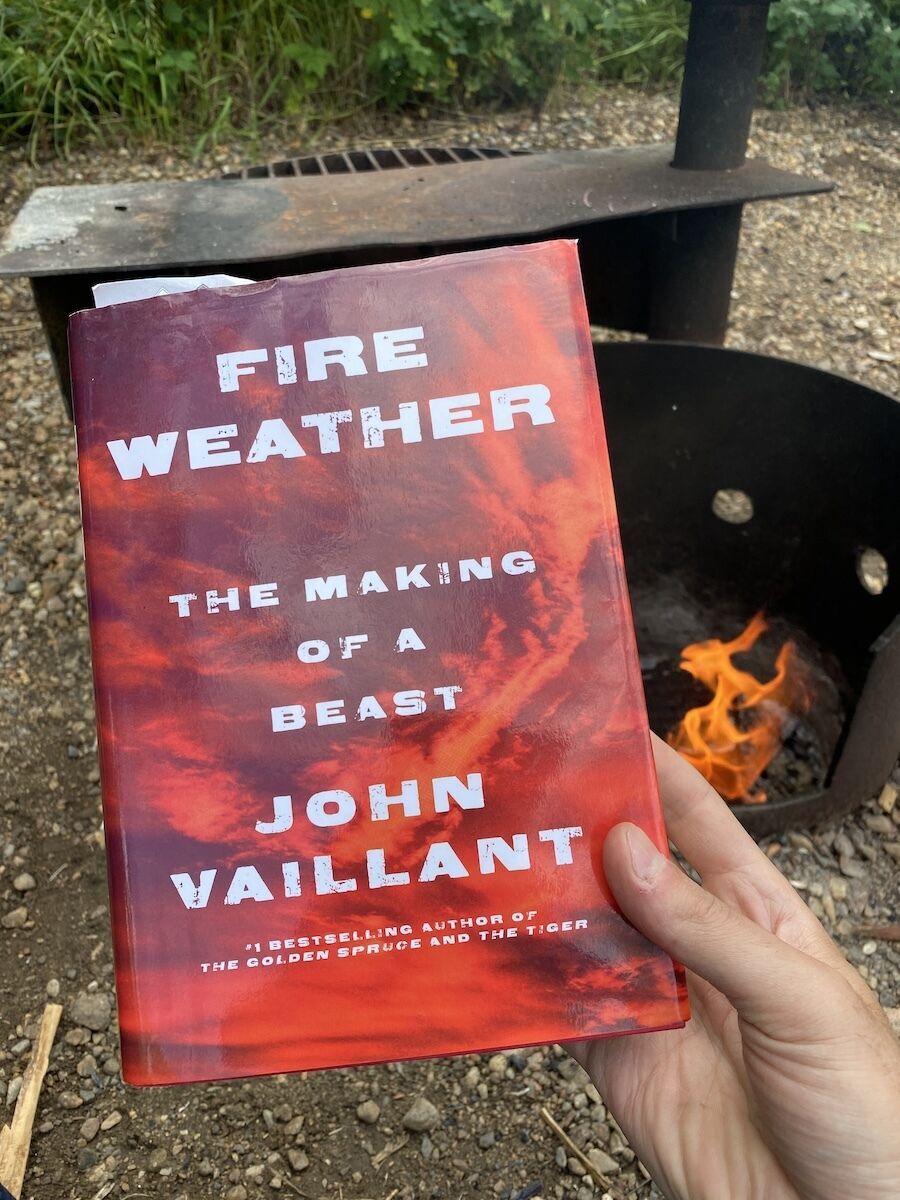

This was driven home for me in a new way this week. While on a road trip to Saskatoon to visit friends, I finally read John Vaillant's book Fire Weather, about the massive wildfire that bore down on and burned through Fort McMurray in 2016. The Canadian subtitle is "The Making of a Beast" but it is the subtitle of another edition that is more incisive: "On the Front Lines of a Burning World."

Hotter days, water shortages, the life-altering impacts of climate change — they were some problem in the distant future.

The best journalism connects the dots, bringing clarity to what can otherwise be hard to see (or convenient to ignore). Fire Weather does that. It is shocking, unsettling and unflinching—connecting the dots between Alberta's petroleum industry, evangelical Christianity, climate change, our historically unprecedented expectation of cheap and abundant energy, and the hotter temperatures and wildfires that are now normal.

Even now, as I write this, more than 1,000 people in Northern Alberta are evacuated due to wildfires.

I'm a slow reader and I read Fire Weather in a few days. It's a page-turner for sure.

But, as compelling as it is, you don't have to read Vaillant's book to know the problem at hand. If you're in Calgary today, all you have to do is go outside and look up at a sky faintly hazy and discoloured with smoke.

And while our drought and river flow levels in Calgary are normal at the moment, Alberta has 22 water shortage advisories around the province—and the situation in Calgary could easily change as we move into late summer, the driest part of the year.

What I realized, working on the latest Sprawlcast, is that the long-term precarity of Calgary's water supply has little to do with the Bearspaw feeder main or any other pipe in our system. This infrastructure is hugely important, of course, and clearly needs better upkeep. But even the best water pipes in the world will be of little use if we don't have enough water to fill them with.

The late University of Alberta water scientist David Schindler sounded the alarm in 2006. "Sometime in the coming century," Schindler wrote, "the increasing human demand for water, the increasing scarcity of water due to climate warming, and one of the long droughts of past centuries will collide, and Albertans will learn firsthand what water scarcity is all about."

To a water expert, looking ahead is like the view from a locomotive, 10 seconds before the train wreck.

So make sure to check out the latest Sprawlcast (you can listen or read, as you prefer) if you want a deeper understanding of Calgary's water supply—and how Calgarians' use of water has changed over the years.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. If you value independent local news, support our work so we can keep digging into municipal issues in the run-up to the 2025 civic election—and beyond!