Calgary 2010: our forgotten Olympics

“The Olympics aren’t the way they were,” said bid boosters in 1998

Long before the IOC started talking about a cut-rate, no-frills Olympics, Calgary had drawn up a plan for just that.

In retrospect, Calgary’s bid for the 2010 Olympics was ahead of its time. It didn’t get far; Vancouver snatched those Games away and the rest is history.

But the failed Calgary 2010 effort, long since forgotten, is an illuminating bit of civic history given our current Olympic pursuits.

The Calgary 2010 bid team didn’t present the Olympics as a way to boost the local economy. In fact they actively contrasted their bid against this approach.

“Often potential cities use their bids as a catalyst for economic development, infrastructure upgrading, job creation and increasing tourism,” reads the Calgary 2010 bid book.

Calgary 2010 was about keeping things lean and supporting Canadian athletes—what promoters called a “new model” for the Olympics.

Calgary’s ‘new model’

In 1998, the city was still riding high on the success of its Winter Olympics a decade prior. With Calgary thriving as a training and competition hub for winter sports, a group of local boosters envisioned a no-frills repeat of 1988.

They polled Calgarians on hosting another Olympics, and what did they find? Most Calgarians liked the idea: 88%, to be exact. It was too perfect.

We can reuse venues, the bid team reasoned. We’ve got a proven track record as a host city. And the IOC, they believed, had changed and would support reusing venues instead of building new ones. The IOC was big on sustainability after outcry over environmental destruction in and around Olympic cities such as Albertville, France (1992).

“The Olympics aren’t the way they were,” said Patricia Trottier, chair of the Calgary bid committee, in 1998. “The IOC has really embraced environmentalism as the third pillar of Olympism.” Trottier and the Calgary 2010 team argued that it would folly to build another set of bobsleigh runs, ski jumps and speedskating tracks in Western Canada.

Indeed, mayors of seven previous and upcoming Olympic host cities— including Calgary, Nagano and Salt Lake City—had just written a joint Olympic declaration along these lines.

“Existing facilities should be used as much as possible in order to lessen the impact on the environment, and the construction of new facilities should be minimized,” they wrote.

Sound familiar?

This is what the IOC just told city council and media during their January visit to Calgary. But Calgary and other cities have been saying this to the IOC for decades, long before the IOC started repeating it back.

In 2014, more than 15 years after the Calgary 2010 bid, the IOC decided it would “actively promote the maximum use of existing facilities” as part of its Agenda 2020 reforms.

Best bid for Canadian athletes

With 1988 still recent, Calgary 2010 organizers proposed only one new facility: a multiplex at Canada Olympic Park with six sheets of ice, a 1.1-km indoor cross-country ski loop and hypobaric sleeping chambers for athletes.

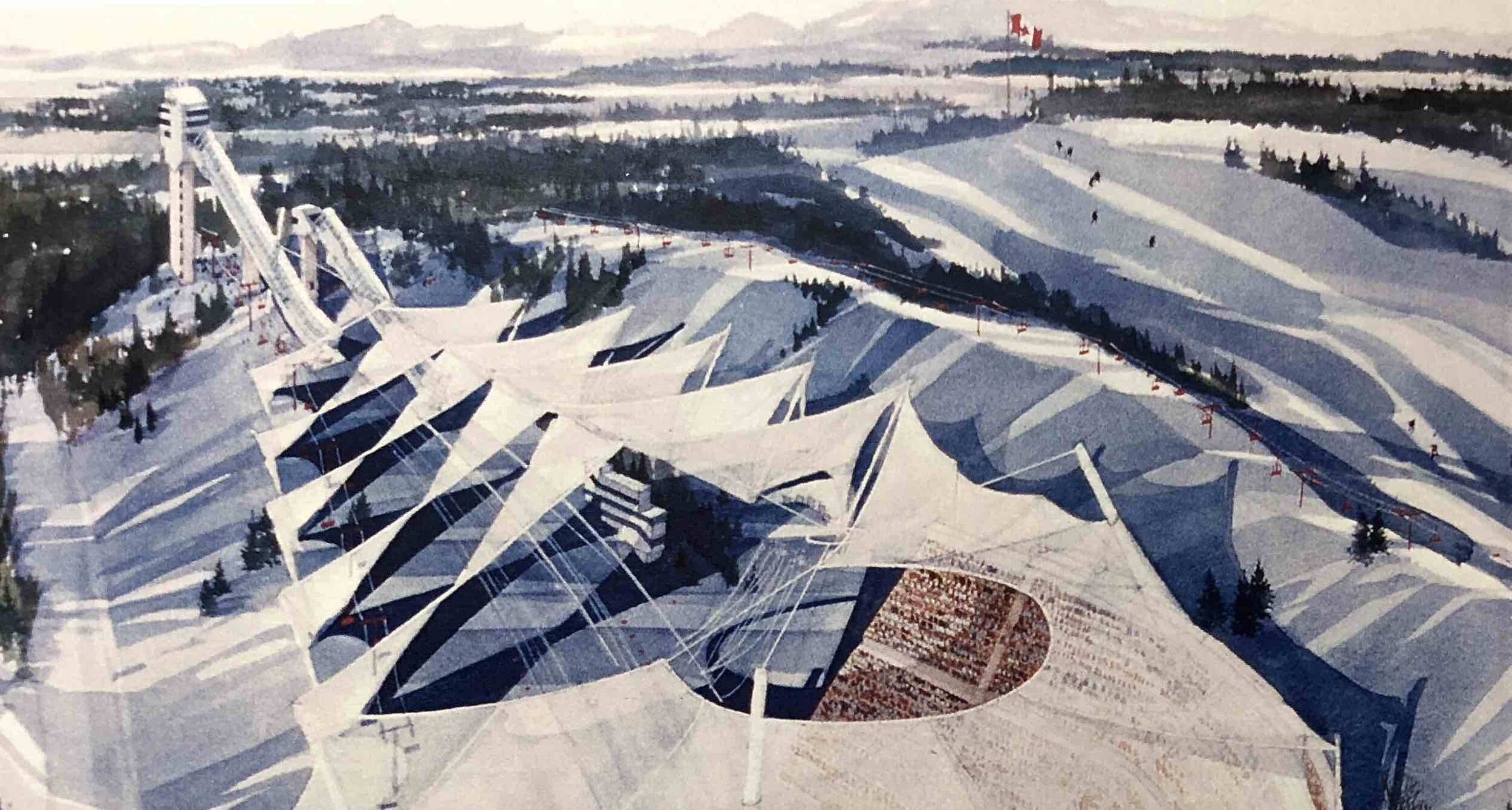

The proposal’s most intriguing image was a retrofit to the ski jumps at Canada Olympic Park.

To protect the slope from the blasting chinook winds which plagued the jumps in 1988, they planned to cover the flight path with a series of five overlapping Teflon-coated wings suspended by cables. (The proposed material was of the same kind used at Hawrelak Park in Edmonton.)

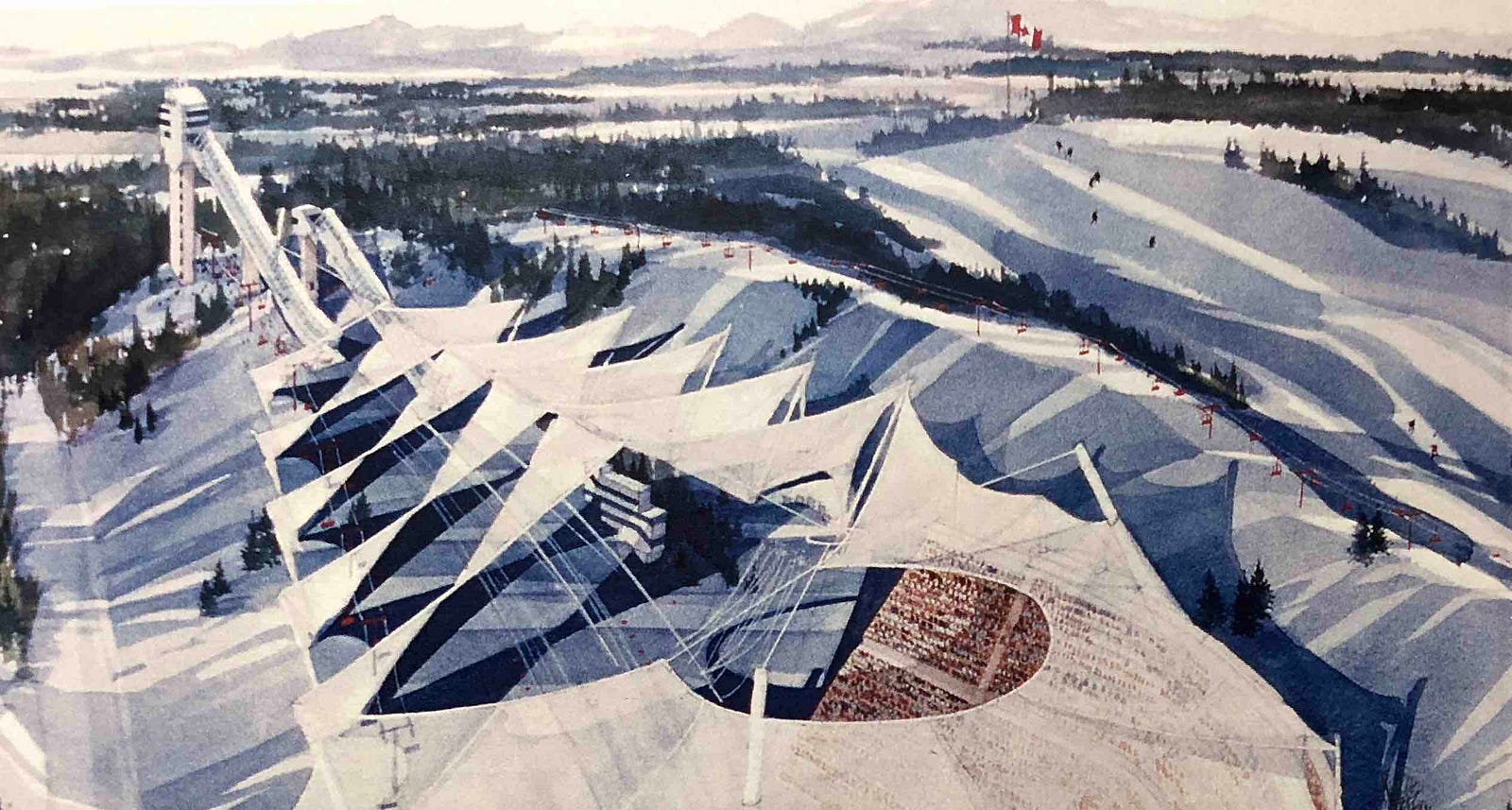

By reusing venues, organizers predicted Calgary 2010 would have a $246-million surplus—and this could be invested into Canadian athletes, coaches and programs. They boasted that the Games would need no government funds.

And by framing their pitch as Canada’s best bid for athletes—low risk, high reward—the Calgary 2010 team hoped to win over the Canadian Olympic Committee (COC), which was also looking at bids from Vancouver-Whistler and Quebec City.

“This approach is an innovative departure from any previous or current Canadian bid, in which taxpayers and government have been expected to underwrite, or guarantee, Games expenses and any infrastructure upgrades specific to hosting the Games.”

— Calgary 2010 bid (circa 1998)

This is radically different than what’s on the table now. The bid committee that looked into a Calgary 2026 Games has predicted that another Calgary Olympics would require $2.4-billion in funding.

About athletes, not the economy

The Calgary 2010 team had a champion in Alberta Premier Ralph Klein, who was mayor when the Olympics came to Calgary in 1988. He praised Calgary’s “financially responsible” plans for 2010.

“This is about athletes,” Klein told the Calgary Herald.

“It’s not about an opportunity to spend huge government dollars again to upgrade a city’s infrastructure or to kickstart a regional economy.”

—Premier Ralph Klein on Calgary 2010

Ultimately, the Calgary 2010 proposal lacked flash. It was unsexy, and it was doomed.

But it’s more or less what cities are looking for nowadays. Before the citizens of Innsbruck, Austria, killed a 2026 bid with a referendum last year, there was talk them holding a back-to-basics Games that would require no new buildings.

“Innsbruck and Tyrol have the potential to be a pioneer of modern, sustainable and moderate Winter Games,” read a feasibility study on 2026, according to Deutsche Welle, the German public broadcaster.

Calgary might have been that pioneer, had it won 2010.

But those were different times. Leaders in the Olympic movement weren’t looking for a cut-rate Games like they are now. And the COC wasn’t keen on putting forward Calgary again so soon after 1988.

And so, where there had been jubilation in 1988, there was now bitter disappointment in Calgary. The COC overwhelmingly chose Vancouver-Whistler for 2010. Calgary came in last on the ballot, behind Quebec City.

Today, there is no such race in Canada for the 2026 Games. Calgary is the only city pursuing it.

Best Olympics ever!

Of course, Calgary 2010 was all on paper. The reality could have—no, certainly would have—turned out differently. Forecasts are always rosy at the outset, untarnished by cost overruns (which have plagued every Olympics, without exception) and unforeseen complications.

The Calgary 2010 Games are a little like the Montreal Expos’ amazing 1994 season, which got cut cruelly short by the baseball strike. Because the postseason never played out, all the best things can play out in our minds.

The Expos would surely have won the World Series that year, bringing baseball glory to Canada for a third straight year.

And Calgary 2010 would have been the best Olympics ever.

Jeremy Klaszus is editor-in-chief of The Sprawl.

This story is part of Hindsight 2026, a joint project between the Sprawl and the Calgary Journal (which is produced by journalism students at Mount Royal University). We’re digging into past Olympics to evaluate whether a 2026 Winter Games in Calgary would help or hinder our city.

Support independent Calgary journalism!

Sign Me Up!The Sprawl connects Calgarians with their city through in-depth, curiosity-driven journalism. If you value independent local news, support our work so we can keep digging into municipal issues in the run-up to the 2025 civic election—and beyond!